Producer’s Note: This post collates a few comments about ‘Wood for the Trees,’ a series about woods, trees and tree planting from Tom Barnes and Charly Le Marchant.

Wood for the Trees is on Youtube, Facebook and Vimeo, with more about why we made this series, and links to information about Tom, Charly and our guests, at woodforthetrees.uk

The series has received many positive comments, “Brilliant, more please.” is heartening to hear, but the more challenging comments are interesting and we did want to spark a debate…

In part two of #WoodfortheTrees Tom spoke with Dougal Driver of Grown in Britain about forest management, trees and British timber. youtu.be/0LO5o15qdVM He talked about the impact of pests and disease on British woodland.

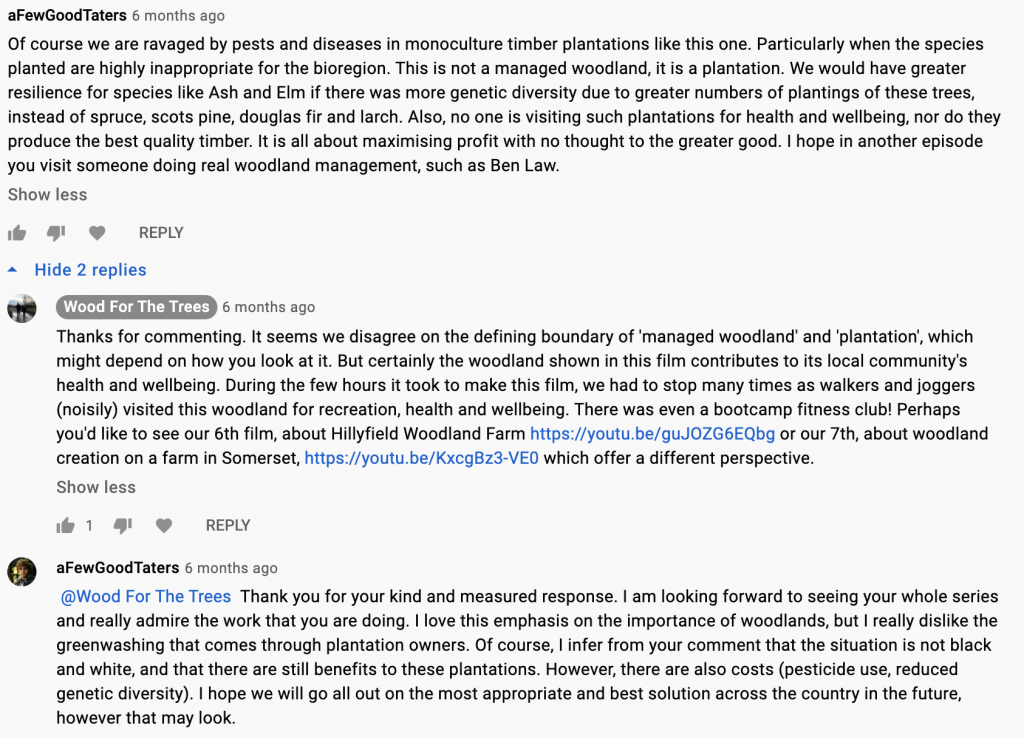

A youtube commenter said “this is not a managed woodland it is a plantation.”

‘aFewGoodTaters’ says “of course we are ravaged by pests and disease in timber plantations like this one. Particularly when the species planted are highly inappropriate for the bioregion.”

I replied (that was me, assistant producer Jenny, having checked the message with Charly and Tom) that we may disagree on defining boundaries, and that there were in fact lots of visitors to this particular woodland for recreation. The joggers disrupted filming several times! Mr Taters reply was generous but wary of greenwash. He said he looks forward to the series and “while there are benefits to plantations there are also costs” such as pesticide use and reduced genetic diversity.

There was a similar comment on this film recently:

“All this talk about “management” the problem with forests in the UK is that most of them aren’t forests, they’re timber plantations. Sitka Spruce, Larch, and Douglas Fir are all non-native species that are not the great boon to wildlife the timber industry claim. Animals don’t live in planations because they want to; they live there because that’s the last place they can cling to. Not one of those species of tree can host the thousands of bugs, birds, bats, and fungi that are specifically adapted to or dependant on native British trees, like oak and ash, and Scotts pine, one of these trees is worth a hundred non-native timber crop. Timber forestry also doesn’t produce healthy long-lived forest, it produces a crop that is harvested, dead trees aren’t left standing denying the ecosystem vital dead wood, fallen trees are dragged away denying the soil valuable nutrients and denying the ecosystem yet more niches. Also, notice that nowhere in that entire plantation in this video are there any shrubs or other middle story trees like hawthorn, blackthorn, holly, or rowan, there aren’t because they are cleared away because this isn’t an ecosystem, it’s a tree farm and an entire trophic level and entire ecological niche is stripped away. That’s what a “managed” forest turns into because forest management is still in the 20th century.”

We replied: You might find this film interesting, part 10 of our series shows rewilding at Knepp. Is there hope of finding an appropriate balance that supports nature as well as producing timber for construction?

Part eight of the series was on the work of the Future Trees Trust, to select the best genetic material to grow future forests for timber production.

One comment says “Please send this film to the Woodland Trust, and all the other bodies who ignore the timber possibilities of woods. Timber can be produced in a multiple-use forest, but planting good growing stock is essential to help with both the economics as well as the justification of tying land up under trees in an ever-hungrier world.”

An youtube commenter suggested it is “pointless”

“Planting oak, chestnut & sycamore in England, whether quality trees are not, is a pointless waste of carbon, time and money! When are folk going to wake up to the reality that, without a nationwide plan to eradicate the grey squirrel (or significantly reduce numbers), the only trees we can grow to maturity are those that are grey squirrel resistant (e.g. Douglas, Spruce,…)?”

And in part nine, we looked at the issues of squirrel control, a film which had a few comments along the following lines;

“Are there options for stands that have heavy squirrel damage? Or is it best to cut your losses and replant?

Part ten, on Rewilding, has only been out for a couple of weeks. But this comment caught my eye: “we need a paradigm shift in how we think to consider the more logical options rather than what we want.”

The debate continues on social media, or you can send comments via woodforthetrees.uk